The Truth Behind Ambition is a no holds barred, three-part autobiographical series sharing guidance, lessons and tales from the other side of entrepreneurial success.

I wanted to run my own business ever since I could remember. Growing up in Russia in the early 90’s (I’m talking 1991 – 1993), my childhood was spent in Moscow during the breakdown of the Communist regime. The combination of the bad harvest in USSR, and the US backed increase in Saudi oil production (the more things change, the more they stay the same…), and consequent oil price fall meant the union could not buy grain to feed its population and quickly this sent the country into bankruptcy. Together, with careful manipulation of the young Russian population and staggering, unrestrained, greed of our political elite, the Balcerowicz Plan was successfully introduced and rapidly plunged the nation into poverty and anarchy.

The sense of social breakdown was everywhere. My most vivid memory is walking around to the entrance of the building where my family had their apartment: a heroin dealer was operating from one of the floors so often the place was full of junkies; they had a habit of breaking the elevator by melting all the buttons with their lighter (to this day – no idea why…). Since our flat was on the 13th floor, the walk was usually long but kicking used syringes down the stairs was a great way to kill time on my way to primary school.

On the streets, the situation was no brighter. I vividly recall walking through the market and seeing a drunk WW2 veteran, medals of honour plastered on his old jacket shining brightly in the setting copper sun, walking through the crowds of grandmothers arguing over the price of rotten tomatoes, begging for someone to buy an old pillow which he was clutching in his hands so he could eat. At the time, pensions were paid irregularly, if at all. To make ends meet, my grandmother – who was a chemistry professor – and I would pick bottles and give them to the bottle bank. The guy who ran it gave us good rates on the bottles as he was my grandmother’s friend and previously used to run one of the major rocket manufacturing complexes in the Urals responsible for many of USSR’s major space race victories (virtually all manufacturing and research institutions were at the time in total disarray).

Yet in in this atmosphere of despair and misery a certain energy of opportunity electrified the cold winter air. Yes, everything was broken but at the same time – everything was possible. Young guys, dressed in black leather jackets were jumping out of trucks carrying TVs, jeans and foreign products to sell to a new generation of consumers. Everyone was talking about business, capitalism and opportunity. Money was everywhere (even through most people had none) and everything was for sale.

Furthermore, since everything was priced in dollars (rouble inflation was hitting 3 digits annually) I remember at six years old knowing most exchange rates by heart and on a daily basis would surprise adults during dinner conversations – “The dollar is 859 roubles today!” (I still remember that “859” figure now….).

Skipping forward a few years, I found myself in England where my parents worked as scientists for the UK government. Growing up on a council estate in Bristol I always wanted “more” than my social environment at the time could provide so since 16 I have been running businesses (graphic design agencies, music production – you name it).

By my early twenties and straight after graduating university I found myself working for a global investment bank in the city of London. I viewed this experience purely as an extension of my higher education as I realised that if I wanted to start a serious business I needed to understand how these worked on a higher level from a financing and strategy perspective and I wanted to learn from the best. Within Investment Banking there are several departments and I chose mergers and acquisitions. That division in particular deals with analysing large companies to prepare them for sale or disposal – a sort of estate agency for businesses with slightly more number crunching. I will not dwell too much on my experience there as although there are some funny stories I might touch upon in later posts, there is not much you can say that has not already been very well articulated in books like Liars Poker and Monkey business.

Although making £100,000+ per year at 25 whilst working on complex billion dollar transactions seemed like a fun and rewarding idea initially, I realised that my entrepreneurial ambitions were taking over and that I could no longer sit in the office dedicating my life to creating slide decks for my bosses 80 hours a week. I had too many ideas, too many dreams and too many well laid business plans that were going to succeed and make me staggeringly wealthy the minute I left that door.

It must be mentioned here that no matter how entrepreneurial you think you are or how strongly you may think you hate your job, it is extremely hard to leave investment banking after 4 years. This is after all an industry where you are making enormous amounts of money (comparative to your peer group), that is well regarded in social circles and one in which staying for 6 – 7 years will inevitably result in a 7-figure paycheck.

What clenched it for me was that I needed to be the master of my own destiny and that by this stage I was pretty much unemployable.

Investment banking demands almost military-like obedience to your bosses who want a total sacrifice of your personal life (for the good of showing your face in the office) and on a fundamental level, I felt this was a bad use of my time on this planet.

(Wait, so you want me to sit here until 3 am, adding these pointless slides to the presentation, because the “client”, in passing, mentioned it could be interesting, but you and I know they have zero relevance to the deal and you agreed because you could not say no? Well, ok… I’ll say no for you).

With that in mind, I left banking to set up my first business. In fact I was working on 3 separate start-ups ideas when I left the bank:

1) online gambling start-up (premise: bet on anything and set own odds – kinda like an eBay for gambling)

2) a biomass power station (15 MW biomass plant in Hull; I still remember taking holidays from my banking job so I could sit around the roundabout in Hull – which was also next to the prison – and in the cold, never ending rain, count the number of trucks going around the roundabout so that I could write my own traffic statement. An essential part of the planning application for the plant.)

3) Raise funds for a general investment company / advisory business for various projects including real estate (and would also introduce investors to deals with a fee for the introduction)

As fate would have it #3 received most traction and we managed to raise money for real estate projects, and to also secure several multi-billion dollar projects to sell (from which we could get very lucrative commission).

Although ecstatic to get hold of capital at first, and itching to put it to good use, nothing could prepare me for the absolute roller-coaster of emotions that I was about to experience.

Now what is less understood about the investing world is that even though you might have access to £millions worth of capital for investments, you don’t actually make much money yourself until you have invested it and made profit.

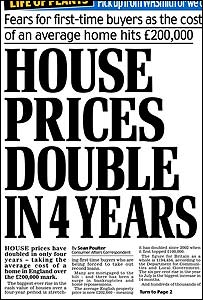

Since our first deals were real estate focused, we had to buy a property, rework it and then sell at a higher price than purchase and construction cost to make our profit. Sounds easy, right? But the market was booming so fast on its way to recovery from the 2008/09 crash that our valuations of purchase prices for buildings that “made sense” were far out of what less rational buyers were paying to secure assets.

I remember one particular situation where an old building in North London went for sale at £6 million. We liked the project and thought that if we invested an extra £1 million to update it we could sell it for £9 million (or £10 million if lucky) giving us a nice, juicy £2-3 million profit in less than 12 months. Hoping to secure the building, we offered a bid higher than the asking price – £6.3 million (£300,000 above asking price). Turns out there were 20 other bidders and the building went for £9 million… (that’s the price we were expecting to sell the finished modernised product). This scenario kept repeating itself for almost 12 months, where each month I was personally bleeding money from my savings account as I was generating no income from the investment business and had to pay rent, food etc.

I remember one particular situation where an old building in North London went for sale at £6 million. We liked the project and thought that if we invested an extra £1 million to update it we could sell it for £9 million (or £10 million if lucky) giving us a nice, juicy £2-3 million profit in less than 12 months. Hoping to secure the building, we offered a bid higher than the asking price – £6.3 million (£300,000 above asking price). Turns out there were 20 other bidders and the building went for £9 million… (that’s the price we were expecting to sell the finished modernised product). This scenario kept repeating itself for almost 12 months, where each month I was personally bleeding money from my savings account as I was generating no income from the investment business and had to pay rent, food etc.

It got so bad that at some point I tallied up the number of deals we tried to participate in and I think it was over 50 live transactions and way over 2,000 opportunities seen in total (the range of investments was rather exotic and not just limited to real estate: helicopter logistic operation set up in China, stakes in Greek fish farms, buying entire LNG fields, sand mines in Thailand, gold trading, luxury apartments in Washington D.C. etc.) – each one having taken days of laborious work and each one having fallen apart due to some unrelated circumstance which ultimately led me to believe it was far too risky to invest in it. [This is actually an important lesson. When making your first investment with money that is not yours make sure you don’t do investment decisions driven by personal greed (or even hunger). If it looks like a potential lemon – don’t touch it regardless of how good it sounds – it probably is a lemon.

Just as the professional side was beginning to grind and drain away my energy, little did I know that the subsequent developments on a personal and financial level would bring me closer to breaking point than I ever would have imagined possible….

The next part of “The Truth Behind Ambition: The Drowning” is available next Friday.