A growing middle class means Angola’s Ghost Town is filling-up, but it still isn’t enough.

When Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos made an election pledge to build 1,000,000 new homes for Angolans in 2008, it was assumed that new-found peace, oil, and chinese cooperation would make for a fairly straightforward textbook task of post-war reconstruction. Luanda, originally designed by Portuguese town-planners to hold 300,000 people, now holds one-fifth of the population of Angola, around 5 million people. Overcrowding, largely caused by Angolans seeking refuge from the mine-fields in the countryside during the civil-war, has made the situation in Luanda desperate and it is widely believed this pledge swung the final election result in his favour.

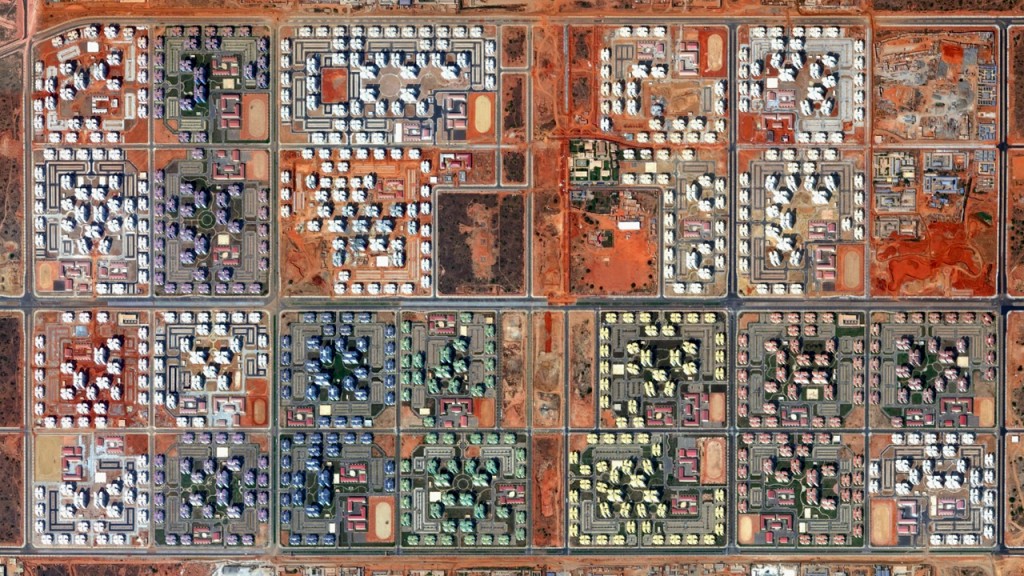

The jewel in the crown of Angola’s new urban strategy was to be Kilamba city, 20 miles from central Luanda. With its own substations for water and electricity and wide boulevards, it was designed to overcome the issues of power shortages, poor sanitation and traffic jams which blight Luanda. The new town was built with Chinese labour as part of a ‘homes for oil’ deal with the Chinese State-owned enterprise Citic Construction Co. Ltd It was designed to finally accommodate 500,000 people, setting the standard for mass-home-building in Africa. Unfortunately for President Santos, it soon gained international infamy as a ghost town.

In 2011 it was reported that only 220 units out of 2,800 had been sold, most remaining completely out of the price-range of even skilled white-collar workers. One scathing critic described it as a ‘natural savanna destroyed to build a human desert’.

Since February, however, an oil boom has seen an increase in buyers for Kilamba. This has been seen largely as a sign of a growing middle-class in Luanda and also that the government has recognised the empty project’s potential to put foreign investment off. A number of buy to rent schemes had been introduced as well as prices being capped at a maximum of $190,000 from $200,000 for larger apartments and $75,000 from $125,000 for smaller ones. It has meant that the development is now popular enough that people queue to make their applications and the private company hired to conduct sales struggles to process 1,200 applications per day.

New buyers are not only attracted by the affordability, they are attracted to the clean living of the complex. The overall layout of the project is reminiscent of early modernist housing designs in the West and has the same air of utopian promise that many developments in war-ruined cities in Europe had after the 2nd world war. The soviet-era potential of the blocks, however, has been largely kept at bay by architectural interventions such as the use of bright colours which strive to give the blocks an identity. There is also the curious use of faux-balconies to give some visual relief, inaccessible to the inhabitants of the apartments, following the Chinese proverb of ‘The Facade of the House belongs not to its owner’. It has mercifully made an effort to encourage retail units and a street scene, something which many gated developments lack, and which can make the streets on the outside of blocks empty and therefore dangerous.

Although Kilamba has grown in population over the last 2 years, it is still only inhabited at a fraction of its final capacity. Despite growing, Angola’s high disparity of wealth has left the country with a tiny middle class, leaving apartments such as these mostly unaffordable for the poor and undesirable for the rich and ex-pats. The government’s recent intervention has staved off embarrassment for the time being, but until several more Kilambas are built, supply will continue to be low enough to keep similar developments prohibitively expensive for most. Any government intervention to help buyers would therefore become unsustainable.

Angola is an exciting place for architects and town planners, a dynamic tabula rasa with money from oil which can be used to experiment and build further. In the meantime, however, until poorer people can begin to afford the prices of apartments such as those in Kilamba, the president could consider much more simple and cheaper forms of social housing to fulfill the spirit of his electoral pledge.